A Glimpse at Lane’s “Latent Labor Force”

January 25, 2024

A few years ago on the Oregon Office of Economic Analysis blog, Josh Lehner posted a report called “Oregon’s Latent Labor Force” looking at gaps in Oregon’s workforce participation. The report has gained a lot of traction in workforce development discussions – the idea of taking advantage of our underutilized labor is especially appealing in times of worker scarcity.

If you’re not familiar, the article is worth a thorough read. The upshot is that Oregon could expect to see roughly 300,000 more people in the workforce if three scenarios took place: 1) women’s employment rate matched that of men; 2) each age group was employed at its highest historical rate; and 3) the educational attainment gap for younger cohorts was eliminated.

Lehner’s analysis looks at the labor force trend over time, something it’s difficult to do at the substate level. It is, however, possible to use workforce and demographic data from the U.S. Census Bureau to create a basic sketch of the “latent labor force” for the regions of Oregon.

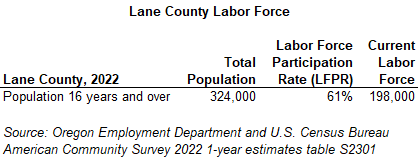

The labor force participation rate (LFPR) is the percentage of the population that has or is looking for a job. In 2022, there were an estimated 324,000 people 16 and older in Lane County. Sixty-one percent of them participate in the labor force, creating a labor force of around 198,000. someone might not seek employment because they are retired, in school, discouraged at their prospects, or for other reasons. We’ll explore four angles on workforce participation: age, sex, disability status, and education.

Room to Grow for Younger and Older Workers

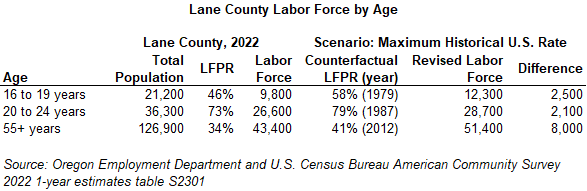

Two gaps exist in labor force participation as it relates to age: older adults and younger adults. For this hypothetical, I looked at what would happen if those age groups participated in the labor force at the same rate they did at their recent historical peak in the U.S. Participation rates for “prime age workers” (ages 25 to 54) aren’t appreciably different from their historical high, so they’re not included here.

Increasingly, young people are substituting education for workforce participation. Even as the employment rate for young people has declined, the rate of young people not enrolled in school and not in the labor force is about the same as in the past. That said, employment of younger workers is noticeably lower now than 40 years ago. Among teenagers, 58% participated in the workforce in 1979, versus 46% in Lane County today, and 79% of people in their early 20s participated in 1987 versus 73% in Lane County today.

The 55 and older population, particularly those 65 and older, is already one of the fastest growing segments of the labor force. However, the aging baby boomer generation means more people reaching traditional retirement age, even as more people work later in life. That pushes workforce participation down, although since the 55 and older population itself is older it’s not exactly comparing apples to apples. In 2012, participation was about 7% higher in the U.S. than in Lane in 2022.

If current labor force participation for these young and old age groups were to match historic highs, it would add more than 12,000 workers to the Lane labor force, an increase of 6%.

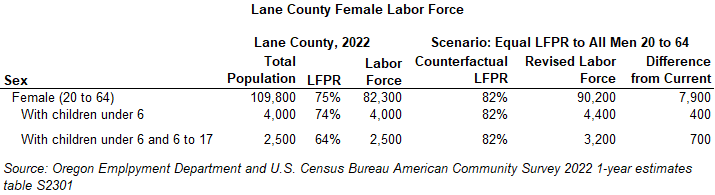

Working Women and the Role of Childcare

In Lane County, the workforce is roughly 50% female. Still, there’s room for growth – women’s labor force participation from the ages of 20 to 64 is about 75%, versus 82% for men. This hypothetical imagines that women’s participation matched that of men, which would bring about 7,900 women into the labor force, a 4% increase.

There’s evidence that women with young children are less likely to participate in the labor force. Women in Lane with children under age six have a 74% participation rate, while those with both young kids and kids between six and 17 participate at 64%. For women with only older kids, the labor force participation rate is actually higher than average.

If women with young kids participated at the same rate as all men, it would bring more than 1,000 workers to the local labor force, despite being a relatively small portion of the population (only 6,500 women total).

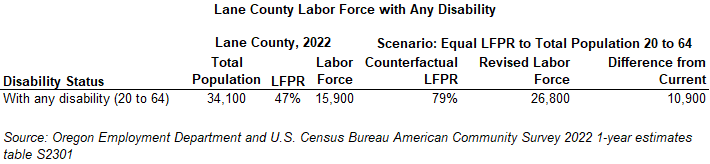

Disability – A Large but Disparate Category in the Labor Force

In Census data, the category “people with any disability” represent a very wide range of impediments to daily life, from ambulatory difficulties to hearing and vision impairment to an inability to live independently. Participation in the labor force isn’t always the end goal for someone with disabilities, nor should it be. Without making a normative claim about who “should” be working, it is interesting to see the possible impact to changes in labor force participation.

About 47% of people aged 20 to 64 with a disability participated in the labor force. If people with a disability had a LFPR equal to the total population in that age range, it would bring nearly 11,000 more people to the local labor force, a 6% increase.

Some of the gaps in workforce participation represent unequal access to the labor market, to be certain. Other gaps represent necessary accommodations for people who cannot access general job opportunities. Given the size of the population with a disability and historical barriers in accessing employment, though, it’s worth looking deeper into what helps people with disabilities take part in the labor force.

Workers with Less Education Are More Likely to be Out of the Labor Force

Generally, less educated workers participate in the labor force less than similarly aged workers with higher education. The local industry mix matters, but in Lane as well as the U.S., changes to industry structure have deemphasized routine mechanical skills, making education from high school and beyond more important to employment.

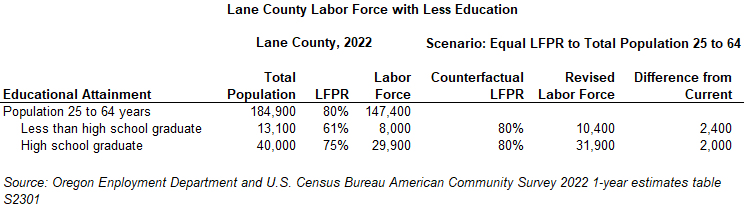

Lane’s LFPR for 25 to 64 year olds that graduated high school is 75%; for those that didn’t graduate the LFPR is 61%. Bringing those up to 80%, the rate for the total population age 25 to 64, would increase the Lane labor force by 4,400, an increase of 2%.

Although the population that didn’t graduate high school is relatively small in Lane County, the substantial increase in LFPR would bring in more workers than the relatively small change to labor force participation for high school graduates.

Expanding Our Reach to the Latent Labor Force

There are many demographic gaps in workforce participation, and it wouldn’t be achievable or even desirable to close all of them. For example, many people 65 and over are happily retired and not interested in working. Anyone should be allowed to participate in the labor market if they choose but expecting 70-year-olds to hold jobs at the same rate as 30-year-olds isn’t reasonable.

There are also demographics excluded from consideration in this article, a key example being race and ethnicity. There are substantial differences in access to jobs, unemployment, and particularly earnings by race or ethnicity, but in Lane County that is not really a question of labor force participation, which is higher in most communities of color.

Who participates in the labor force and why is a tricky question that we can’t change with a wave of our magic wand. Still, understanding where gaps exist and the impact of closing them is an important first step to outreach and inclusion in the job market.